I keep coming back to the artistic vibrancy framework in my work for arts organisations, and hearing of how it has been adopted across Australia and overseas. I thought it might be time to unleash my Onion of Artistic Vibrancy on to the unsuspecting arts world.

I keep coming back to the artistic vibrancy framework in my work for arts organisations, and hearing of how it has been adopted across Australia and overseas. I thought it might be time to unleash my Onion of Artistic Vibrancy on to the unsuspecting arts world.

When I was at the Australia Council for the Arts, I worked with the performing arts sector to develop an artistic vibrancy framework. For a long time, the arts organisations and funders had struggled to articulate artistic merit. We needed a shared language to talk about, and to some extent, evaluate, measure or at least record, artistic vibrancy.

We identified five core elements of artistic vibrancy:

- excellence of craft

- development, preservation or curation of the artform

- development of artists

- audience engagement and stimulation

- relevance to the community

Excellence of craft

This is about how well you do your art – eg your technical proficiency as an orchestra or the production values of your play. Your peers are probably the best people to ask, eg through peer review, benchmarking against organisations you are like or which you aspire to be like, or less formal conversations.

Development, preservation or curation of the artform

This refers to how well you contribute to your artform. Again, your artistic peers would be the ones to comment on this, as well as the community of the artform you are in and the artists you work with. You could do this via interviews, conversations, a peer committee, and opportunistic conversations eg with visiting experts or well-respected guest artists.

Development of artists

This refers to your organisation’s contribution to the development of artists. Your artistic peers, sector experts and the artists themselves would be the best placed people to talk to about how well you are doing in this area – eg through conversations, a peer review panel, and artist surveys.

Audience engagement and stimulation

This is a question for the audience of your work – either for live performances, readers of your books, or online viewers or listeners to your music. We want to find out how emotionally moved, intellectually stimulated, challenged and captivated they were by your artwork, coining Alan Brown’s language or artistic impact. The best people to ask about this are the audience members, via interviews or a survey.

Relevance to community

This is about your organisation’s connection to its community beyond the audience. For example, an orchestra can be relevant to its wider community through education programs, or perhaps through programming decisions to engage target groups. “Community” can be your organisation’s target communities, eg disadvantaged youth or particular ethnic groups, or it could refer to your local community or your entire nation. The key question is to ask how relevant you are to these people. And the best people to ask are naturally the community members you are interested in connecting with. You can do this via open days, community surveys and community consultations, or perhaps conversations with community representatives.

The above is a quick summary. There are four papers I wrote about it, and a whole “Artistic Reflection Kit” designed to help organisations reflect on their own artistic vibrancy, available on the Australia Council website.

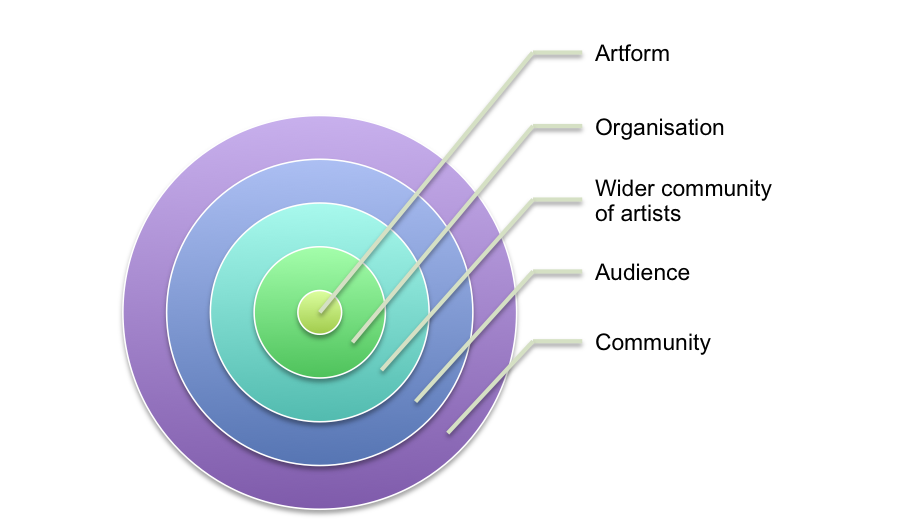

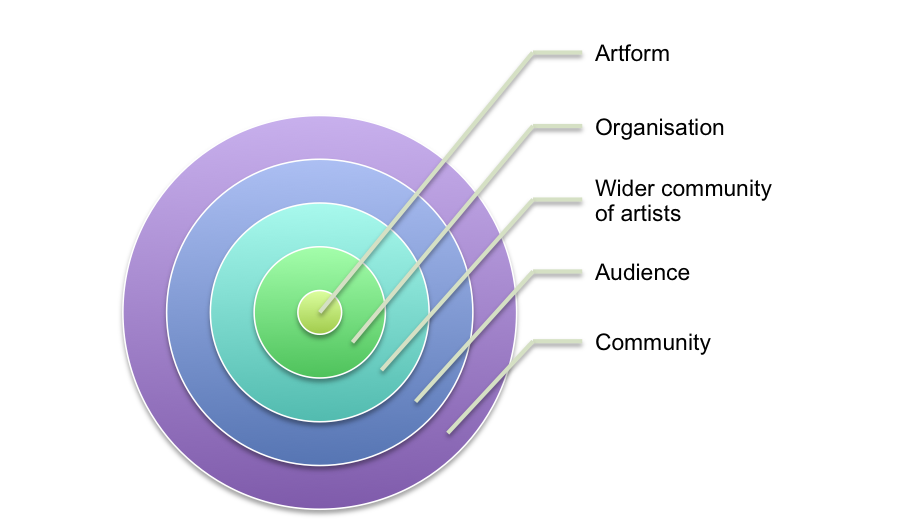

The onion of artistic vibrancy

Now we come to the onion.

My underlying idea when developing the artistic vibrancy framework, is that arts organisations are all about relationships.

We can think about these relationships as a series of concentric circles, like an “onion.”

At the core of the onion is the organisation’s relationship with the artform itself. For example, ‘excellence of craft’ is really about a strong relationship with the artform, as is the ‘development or preservation of the artform’.

At the next ring out is the organisation’s relationship with itself. This includes the organisation as an idea, a brand and an institution, as well as the organisation’s more tangible connection with its own staff, both artistic and non-artistic.

Then we move to the organisation’s relationship with artists who may be external to the organisation, and the wider artistic community. The organisation always sits in relation to its “field,” to be Bourdieu-ian about it.

At the next level is the organisation’s connection with its audience – those who watch, listen and experience the art.

Then we have the ‘community relevance’ layer, which is the skin, the interface between the ‘inner onion’ and the wide world. This is about the relationship of the organisation and its work with its identified community and specific communities of interest.

And then there is the air, the wide wide world in which the onion sits – the connection with the general public.

Why the onion is a useful tool

By conceptualising it this way, arts organisations can start to map their own efforts and energy when it comes to each dimension of vibrancy. If you wanted to, you could actually draw an onion and map your resources and programs on to it, to see where you might be strongest or where you might want to concentrate more energy.

The layers don’t have to represent waning connection the further out you go. Your aim is to have strong weaves between all layers.

This could be a useful way of communicating your organisation’s foci to others. Importantly, it is a good way to understand yourself, keeping the art at the heart of the onion but strongly weaving its connection to all layers.